Mojo

REMEMBERS

Jimmy Cliff: “We need music to have a message right now.”

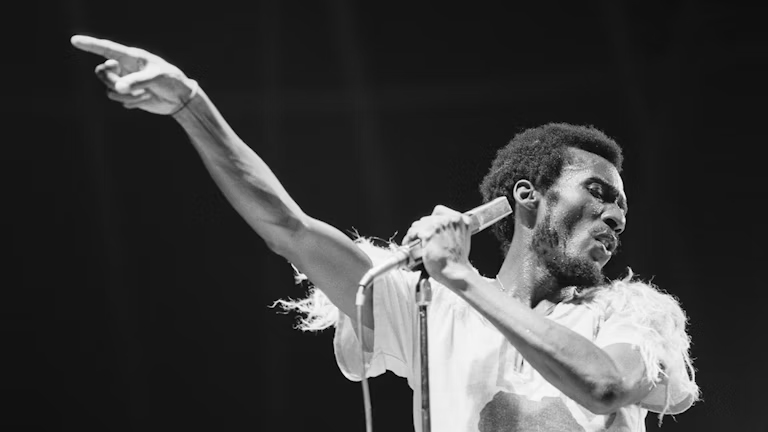

In tribute to Jimmy Cliff, who has sadly passed away aged 81, MOJO revisits our career-spanning interview with the reggae icon

Lois Wilson

Alongside Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff is perhaps the artist who did the most to bring reggae music to the world. Both through international hits such as You Can Get It If You Really Want, I Can See Clearly Now and Wonderful World, Beautiful People, and his starring role in 1972’s The Harder They Come, a film and its accompanying soundtrack that turned an entire generation on to reggae. In 2012, MOJO’s Lois Wilson sat down with the reggae icon to discuss his remarkable life and career. In tribute to Cliff, who has sadly passed away at the age of 81, we’ve republished the interview in full…

Jimmy Cliff takes MOJO’s hand in both of his and in a low, soft voice as if he’s about to confide some big secret he says, “I’ve got my talking head on, I hope you’re ready for some stories.” He chuckles at the thought then leads us over to a quiet corner spot in the otherwise bustling restaurant in the Royal Garden Hotel in Kensington, where he’s been staying for the past two days, on a part holiday part promo trip. “It’s been good,” he says, “but I’m looking forward to taking it easy when I get back.” Back being Paris, one of three home cities he resides in these days – the others being Miami and Kingston, where he’s lived since he was 14.

He recorded his latest album Re.Birth in Los Angeles with Rancid’s Tim Armstrong. It sees the singer return to the soulful roots reggae style of the ’70s. “To remind people where reggae came from, and that it is still around,” he says. “It can still be important, it can have a message. Because we need music to have a message right now.”

The man born James Chambers is dapperly attired, in a bright yellow long sleeved top emblazoned with the Lion of Judah, and his name above it, black jeans, a backwards turned brown suede cap, red and brown diagonally patterned socks and red embroidered slip ons. He looks much younger than his 63 years. The secret he says, with a lazy grin, is “a sunny outlook, exercise and healthy eating. I don’t eat meat. My only vice is coffee.” He orders a triple shot cappuccino as if to prove the point. “It aids the thinking, we’ve got a lot to get through.”

And there is a lot. It’s 50 years since Cliff recorded his first Jamaican hits, Dearest Beverley and Hurricane Hattie for producer Leslie Kong, but it was after a move to London under Chris Blackwell’s instruction that he started to make his name in the UK. 1969’s Wonderful World, Beautiful People (“my philosophy”), the same year’s Viet Nam (“someone had to write it”) and Many Rivers To Cross (“my story”) are staples of any reggae greatest hits collection today. Next came director Perry Henzell’s The Harder They Come film of 1972.

Employed initially to pen the movie’s score – he contributed just one new song, the title track – he ended up playing the lead role of rude boy outlaw Ivanhoe Martin, in the process becoming an ambassador for reggae worldwide. Of course it is Bob Marley who is most often attributed with exporting reggae from Jamaica today.

“I don’t mind,” says Cliff, “Bob was a friend, he did a lot, and I did a lot too. But not enough, I want to fill stadiums, I want Number Ones, I want an Oscar, I want to be an international hero. I’m not going to stop until I am.” But before we look to the future, we begin with Jimmy’s past…

What are your first musical memories?

My father was a religious man, so my first musical memories are from the church in Somerton where I was born, the singing, the clapping, the tambourines, everyone got into the spirit, it was high energy and it touched me. Even at three, four, five years of age I knew music could move you.

Where and when was your first encounter with secular music?

That was at the Money Rock Tavern, which was next door to where we lived. It had a sound system called Pope Pius, and it pumped out music all day and night and it was my heaven. I would sneak out behind my father’s back to hear Cuban music and Latino music, then we got a radio and I got to hear rock’n’roll and R&B.

Fats Domino was a favourite.

He made a big impression. Later down the line I got into Sam Cooke and Ray Charles. I don’t know what made them connect, if it was their voices or the rhythms or what they were singing about, but they touched me deep.

How did you make the leap from listening to music to writing your own songs?

I was in school and I heard a local artist on the radio. His name was [ska/reggae pioneer] Derrick Morgan and I liked the song and I asked my woodwork teacher Mr Stewart, ‘How do you write a song?’ He told me you just write it, so I went ahead and wrote a few songs. I wrote a song called I Need A Fiancée (laughs), another called Sob Sob and I made a guitar out of bamboo to accompany myself.

The next step was to make a record. In Jamaica you walk up to a producer’s home, knock on his door and ask him to record you. Wasn’t that a bit intimidating?

It was just what you did. You found out where the sound system operators were and you walked up morning, noon or evening and asked for an audition. You went back on the day they told you to and they’d be a long line and you’d wait, you’d have no food to eat, it would be hot, you’d want a drink of water and at some time you’d get to sing. At first I went to the big ones, Sir Coxsone Dodd, Duke Reid, King Edwards, they said no, so I went to Count Boysie, he was a smaller operator in Kingston. He liked my voice and he recorded my song Daisy Got Me Crazy. It was a good feeling being in the studio for the first time.

How did you strike up with the producer Leslie Kong?

One night I was walking down Orange Street, checking out sound systems to try and get another record cut, and I looked up and saw Beverley’s Records and Beverley’s Ice Cream parlour and it just clicked in my head to go inside and maybe they would record me. I had a song I was writing called Dearest Beverly and I finished the song in my head and I walked inside. They were closing up, but I sang the song, and Leslie Kong said I had the best voice he had heard in Jamaica. He told me to get some singers together for a session. I got Derrick Morgan and Monty Morris and we all recorded and that was Leslie Kong’s first session. They got hits from it, but I had to wait for the second session, to get my first hit with Hurricane Hattie.

For such a small island Jamaica made a hell of a lot of great music.

What else was there for people like me to do? The polarisation of the socio economic scene in Jamaica meant there was hardly a middle class. There was the really rich or the really poor, and if you are really poor, you get a fairly average education in college or primary school, you know the 3Rs – reading, writing, arithmetic – so you can learn a trade, become a carpenter or work on the sugar estate. But for a lot of people they want more. Because the music industry was localised, it was there on the doorstep, people like me started thinking they’d give it a go because you just knock on a door and ask. It was like London in the ’70s with punk. It was like music is for everyone, we can all do it, just give it a try and see what happens.

Were singers considered cool in Jamaica at the time?

Of course, you get girls, and even if you don’t get a hit people know you, they think you are somebody, they look at you and you start getting treated special because they see you as an artist and you see yourself as an artist too so you start behaving as though you are special too.

And as a singer, what did you think you could achieve?

I was imaginative and driven, I thought you could achieve anything you wanted, so I thought I’d be travelling the world and introducing reggae music to everyone, which I did.

You moved to the UK in 1965 after an invite by Island’s Chris Blackwell. What were your first impressions of the country?

The cold, the fog, the damp, it was a shock and coming from the airport I saw all these chimneys on the houses and thought they were factories and I said to myself, No wonder so many Jamaicans come here, there is lots of work (laughs). I didn’t know houses had fireplaces and chimneys. I lived in Earls Court first and one day I finished my morning exercise and the caretaker knocked on the door and asked me what was I doing there. I said, ‘I live here.’ She said, ‘We don’t rent places to coloured people’ and told me I had 24 hours to get out. I replied, ‘if you want me to leave, you got to get me out on my head’ and I slammed the door in her face! Later I moved up to Finsbury Park with my brother and that felt more like home. There was a big west Indian community there, we got to hear all the news from home, we could buy yams, I went to the sound systems, went to the Four Aces in Dalston and The Roaring Twenties in Carnaby Street. It wasn’t the same as in Jamaica, for a start they were inside, but they were still good.

How did the UK shape your music?

Before I came to the UK I was singing reggae, and on my arrival I taught my band here how to play ska but in the clubs they wanted soul music so we had to change the set, we would be playing 60 per cent soul, sometimes more. We played [Sam and Dave’s] Hold On I’m Comin’, [Eddie Floyd’s] Knock On Wood and [Wilson Pickett’s] In The Midnight Hour. Being exposed to that environment, it influenced my own music, I got much more soulful.

Why did you sign to Island?

In Jamaica they said Chris Blackwell paid the best money and there was Jackie Edwards, who recorded for him, riding around on a scooter so we all wanted to record for Chris so we could have a scooter too. When I represented Jamaica at the World’s Fair in New York in 1964, Chris saw me sing and asked me to come to London. He was looking after Millie Small and she had become a smash all over the world. He said, ‘You are a better singer than Millie, so imagine if I can do that for her, what I can do for you.’ I went back to Jamaica and for six months I considered the offer and I finally decided, yes I’d come to London.

Your Island label mates included Traffic, Fairport Convention, Jethro Tull. What did you think of rock music?

At the time I didn’t see a difference between reggae and rock, it was all music and if it was good music it was good music. I knew all the acts on the label, like Traffic, I’d supported Stevie Winwood when he was in the Spencer Davis Group when I first arrived in London, we played the Marquee, and we struck up a friendship, we would talk about soul and blues.

Your 1968 debut album, Hard Road To Travel, included a cover of Nirvana’s Waterfall, an unusual move for a reggae artist at the time. How did you approach it?

I didn’t like the song, but I’d been asked to represent Jamaica in an international song contest held in Brazil and I wanted to go so I said I would sing it because Island wanted me to cover it. Nirvana wrote it, they taught me how to sing it, we did it pop, with an orchestra, I didn’t see it as a change in direction at the time, it was just part of my job, but all the la, la, la, la, la, I couldn’t get into. In hindsight I realise that’s what people liked and remembered about it.

And Wild World by Cat Stevens?

I felt an affinity with Cat Stevens. They tried to market him as a rock act and, like me, he was more than that and one day I went to the publisher and he played me this demo of Wild World and he told me that Steve [Cat’s real name] had written it but he didn’t like it. I loved it right away so he called up Steve and put me on the phone to him. Steve asked what my key was, I said and he started playing guitar down the phone. He said we have to record it together so he went in and did the track and I went in the following day, helped put on the backing voices with Doris Troy and then it was time for me to put my voice on and Steve directed me to sing the high notes on the song. He was a really good producer and it was a big hit.

Could you have achieved the same level of success by staying in Jamaica?

I had to move to the UK to have the big hits. That’s what everyone did who made it. There was only Desmond Dekker who made it without moving, but the door was already opened by Millie Small, and he moved to the UK after the hits started coming for him because in the ’60s London was the creative hub of the world. Besides The Beatles and the Stones, all these other kind of musics were coming out of the city, there was myself, Jimi Hendrix, and you had a lot of Americans, Africans and west Indians coming over to stay. It was all one big exciting mix.

What did you learn from working with Chris Blackwell?

Chris showed me how to open my first bank account in England, and he also showed me how to run a business. When Island moved to Notting Hill, they just had one big room and they had this round table and all the phones were on it and I thought that was really cool, everyone could look at each other and talk and discuss and that taught me that closeness and personal contact in business is important. I also learned confidence, he saw in me what I see in myself, and for him to say I believe in you, come to England, that was an important thing for my self esteem.

How did you get cast in the lead role in The Harder They Come?

Director Perry Henzell sought me out after he saw an album jacket of mine, which had two different photographs on it, one where I looked like a winner and the other where I looked like a sufferer. He told Chris Blackwell if someone could transmit that range in two photographs he would be able to do what he wanted so he came to Dynamic Sound studio in Jamaica where I was recording You Can Get It If You Really Want to meet me and ask me if I could write the soundtrack. Then he sent the script to Island for me to read and then he came to England where I was renting a flat in Cheyne Walk in Chelsea near Mick Jagger. He ran through a scene with me in the front room and once he saw me act, he said you’ve got the part.

How true to life was the film?

Once I got the part we re-wrote a lot of the story to reflect my experiences so the fact that [the protagonist] Ivanhoe Martin comes from the country to the city to seek his fortune are my story. The musical parts are true to. There were two or three giants who controlled the music industry at that time and if you weren’t linked with one of them you couldn’t get anywhere. And the gangsters, we would watch Jimmy Cagney movies at the theatre every week, and the gangs would act out what they saw on the screen and because it was a very volatile political time, we had to be careful where we were shooting and we had to stop many times because one area would belong to one party and another to another party and you’d have to declare your intentions if you wanted to enter the area or risk getting shot at.

What impact did the film’s success have on you?

I became a hero. In Jamaica I couldn’t get to the theatre for the opening as there was a sea of people up to the doors, I couldn’t even get close, let alone push through. I went along the next day to see it, and the rails round the theatre were bent to the ground by the crowd. A week later I saw someone wearing a T-shirt with my face on it. And in London, it was something to see my picture on the bus going by. I became happier, but also sadder, that was the complexity of it. Everyone looks at you when your light is on, for good and bad. Some are jealous and you are open to criticism. It took a while to learn how to deal with that.

What did the film achieve for reggae?

The movie impact on the world was phenomenal. It introduced the music and the culture to a mass audience. We had had Millie Small, Desmond Dekker and Dave and Ansel Collins in the UK but in the States and a lot of Europe they didn’t know what reggae was. I remember when I used to be asked in America, what music did I play and I would say reggae, and they would say, ‘Like Reggie?’ They had this baseball player called Reggie Jackson and they thought it had something to do with him. It was impossible to explain but then after the release of The Harder They Come, they understood.

For all the success the film brought you, you decided to leave Island. Why?

They didn’t know whether to promote me as a pop act or a reggae act and I had had the hits Wonderful World, Beautiful People and Wild World and I thought, now they will promote me like they promote their other acts, but they didn’t so when I saw all the attention I was getting for The Harder They Come and still nothing was happening, and in addition I had put Desmond Dekker on my song You Can Get It If Your Really Want It and The Pioneers on my song Let Your Yeah Be Yeah and both were hits. I decided I better make my move. Then Island signed Bob Marley.

Did you feel Marley stole your thunder?

I was happy for Bob, because I was pushing Bob to Chris, saying this guy is the next Sly And The Family Stone, but when I saw the promotion going behind Bob, I did ask, Why weren’t they doing that for me? Chris said later, he was so bitter about my split from Island that it made him push Bob even more (laughs).

Is it right to say that Trapped on your 1989 album Images was partly inspired by your time at Island with the lyric “Well it seems like I’ve been playin’ the game way too long, And it seems the game I played has made you strong”?

Yes definitely, but it’s not the only aspect of the song. I take the inspiration from my own story and then make it a universal message so the song also relates to personal relationships I have had in the past.

Your songs are often tinged with pathos. Like when you sing on Many Rivers To Cross, “Yes, I’ve got many rivers to cross, But I can’t seem to find my way over, Wandering, I am lost, As I travel along the white cliffs of Dover”. It’s obvious there were dark times.

I left Somerton to go to Kingston to make it, then I came to England to make it and still I hadn’t. I would go to Dover to get the ferry to Calais then the train to St Tropez to sing to people who drank champagne and didn’t care what I was doing. At the same time I was struggling with my identity as an African descendent man, I couldn’t find my place in the bible, and the frustration of the artist and the person fuelled the song. And everyone can relate because everyone at some point in their lives asks, Who am I? Why am I here? What am I going to do? I thought a lot about giving up at this time but the answer was always, and do what? There was no way out, I had to continue.

A common theme for you is self determination.

I grew up in a big family of nine, everyone was vying for recognition, I had to learn quickly how to fight for myself, and that helped to give me that strong character. I always had to stand on my own and be counted.

You’ve never been afraid to stand by your beliefs. Viet Nam was an incredibly powerful protest.

I always felt I could make a change through music, maybe that stems back to the church and listening to Sam Cooke, but I was socially conscious and sensitive to the things going on in that war. A friend I went to school with, he was a great artist, he went to live with family in America, he got drafted, went to Vietnam, and it blew his mind. He came back, he didn’t recognise me, it was as if he was dead.

How did the collaboration with Tim Armstrong come about on your new album Re.Birth?

Joe Strummer was the link. Joe played on [2008’s] Black Magic and introduced me to Tim. He reminded me of myself, he came out of the rebelliousness of reggae and we sat in the studio talking about the sounds we wanted, the instruments we would use, we talked about reggae’s history, and that’s when I wrote the track Reggae Music on the album, which references Desmond Dekker, Prince Buster, Lloyd Knibb. With it being 50 years of Jamaican independence I wanted to pay tribute.

Is that why you decided to return to the roots and rocksteady sounds?

Partly, but I felt there was a chapter that still needed writing. After I had hits with Wonderful World Beautiful People and I made the album Jimmy Cliff, rather than follow up with another reggae album, I found myself on another path. I went to Muscle Shoals and recorded Another Cycle, which was a soul album. I felt I’d never completed the reggae chapter and so I went back to do that with this album.

What do you think of the current reggae scene?

The dominant style in reggae, I call it ‘girls and cars and superstars’, where everyone is singing about sex, it has nothing to do with enlightenment and the uplifting of the people, which is the real roots of reggae. You have some people like Sizzla and Capleton who are the roots torchbearers but for the most part it’s just sex. This album is important because it says, there is another way, reggae can be alive, it can still have an impact, it can still change things.

What has 50 years in music making taught you?

It has helped me realise that my role in life is that of the humanitarian, and that through my music I am trying to make the world a better place.

This interview originally appeared in MOJO 224.