Mojo

Presents

“Zimmy’s Gone Crazy!”

…Or so reckoned Eric Clapton as he walked out on Desire, Bob Dylan’s accidental masterpiece. And no wonder – given the wiped tapes and marital headaches, mobsters and jailbirds, Rolling Thunder and industrial catering. “It was a chaotic, crazy scene,” discovers Michael Simmons.

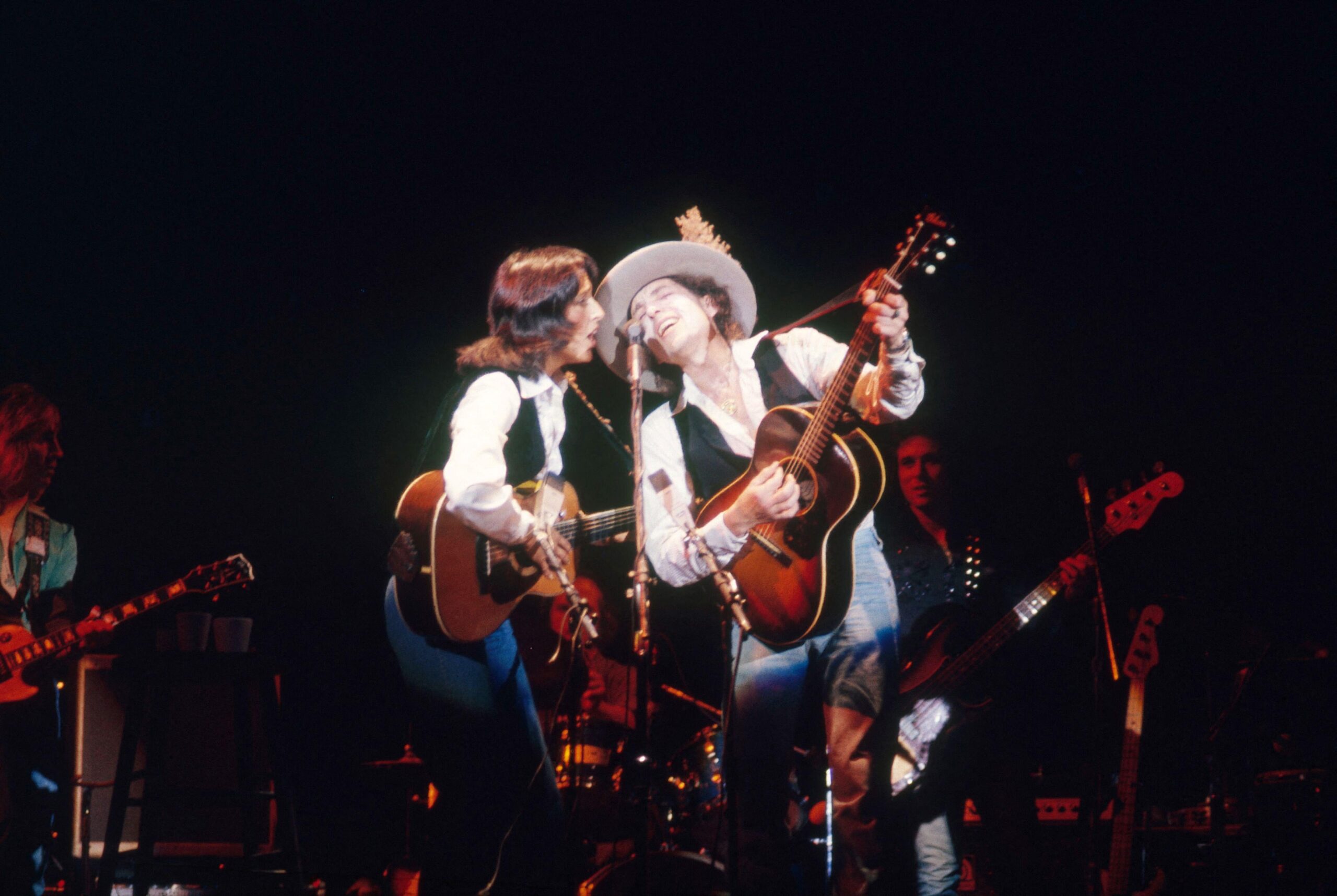

Bob Dylan and Joan Baez in concert during the Rolling Thunder Revue, at the Civic Center, Springfield, MA.

SCARLET RIVERA WAS A YOUNG classically trained violinist recently transplanted from Chicago. A striking brunette with waist-length hair and gigs with Ornette Coleman and a 15-piece Cuban band in Harlem, she was carrying her violin case and preparing to cross a street in Manhattan’s East Village when serendipity struck.

“This car pulled up and the driver asked, ‘Do you play that thing?’” she tells MOJO. “If I had crossed the street seconds earlier, it never would’ve happened. Bob’s very intuitive about people and something made him stop. I realised it really was him and it was okay to jump in the car.”

And so, in the early summer of 1975, the fledgling musician found herself in the company of Bob Dylan, en route to his studio on Houston Street. With Dylan on guitar, then piano, they jammed on some new songs he had. But Bob didn’t sing, he just played the changes. “I was put on the spot to go into the most creative zone I could be in,” she explains. “It wasn’t about thinking. I had to come up with the goods.”

They connected musically, but Rivera kept any excitement she may have felt to herself. “Personally I was a lone wolf, withdrawn and remote and not terribly social,” she says. “I didn’t play female games or scheme how I could sit next to him. He liked that. Those qualities were the reason it worked, equal to my musicianship. It led to a level of trust. As the day progressed, he started to smile.”

They finished up, but the night was young. “He said he had to see a friend of his play and would I like to go along to The Bottom Line?” Dylan’s friend was Muddy Waters. Muddy invited Bob up to play harp and after one song Dylan made an announcement: “I’d like to bring my violinist up.” Waters’ band made Scarlet feel welcome and Muddy gave her a solo.

The signature sound of Desire – destined to be Bob Dylan’s 17th studio album and Byrds founder Roger McGuinn’s “all-time favourite” – had arrived, but Rivera didn’t know it, and neither did Dylan. The singer had other things on his mind, including marriage problems and the first inklings of an under-the-radar concert tour that would become The Rolling Thunder Revue.

“A lot of Desire’s success is accidental,” confirms Rob Stoner, the man who would play bass on it, while Rivera remains “in awe of how it fell together”. A Dylan album unlike any other, described by key contributor Emmylou Harris as “its own thing” with “something rich and romantic and wild about it”, it was not to every Dylan fan’s taste on its eventual release in January 1976. But 50 years on its surging melodies, serving painterly evocations of mythic worlds and real-life tragedies, win out: proof that even when Dylan doesn’t know what he’s doing or what he wants, he’s capable of magic.

“Desire is its own thing, with something rich and romantic and wild about it.”

Emmylou Harris

WHEN BOB DYLAN EMERGED FROM ROAD-RETIREMENT in 1974 for his first tour in eight years, fans rejoiced and the two-month trek with The Band was a popular success, preceded by the Planet Waves album and resulting in the live Before The Flood. What followed in ’75 was more artistically monumental: the wrist-slashing masterpiece Blood On The Tracks and (at last) the release of The Basement Tapes, Dylan and The Band’s ’67 home recordings. But Dylan remained restless. In early 1975, shooting hoops with Roger McGuinn outside the Byrd’s Malibu home, Dylan mentioned an idea that he’d been toying with. “I wanna do something,” he said. “Kinda like a circus.”

“He spent years holed up in Woodstock raising a family,” explains friend and writer Larry ‘Ratso’ Sloman of Bob’s mid-’70s mindset. “Performing has always been his passion. But getting back on the road with The Band wasn’t that satisfying. It was an alienating experience, going from stadium to stadium, not knowing what city they were in. He’s always been connected to the street; there’s a part of him that’s a street guy. He told me about being in Corsica, sitting on the back of a truck, and he realised his destiny was to be back performing in front of people.”

By June of ’75, Dylan had showed up in New York’s Greenwich Village – the centre of his early ascendance – open and energetic, seeing old pals and making new ones. Word got out. “Greenwich Village’s time had passed by ’75; culturally the action had shifted over to the East Village,” says Sloman, referring to punk rock at CBGB and the avant-garde arts scene. “When Dylan came back that summer, he infused a whole new breath into the area. He was hanging around in his old haunts.” Running buddies included musician/artist Bobby Neuwirth and theatre director/psychologist/lyricist Jacques Levy.

Levy had already co-written songs with Roger McGuinn for a never-produced musical based on Ibsen’s Peer Gynt called Gene Tryp, from which came a flock of Byrds songs, notably Chestnut Mare. He lived on LaGuardia Place, around the corner from the Other End nightclub and bar, a hub for singer-songwriters on Bleecker Street. Dylan and Levy ran into each other on the street and Bob suggested they collaborate. Levy was game but expected nothing until his bell rang one day.

They began writing together. Levy – who’d directed the erotic musical Oh! Calcutta! – unleashed Dylan’s theatrical inclination and worked with him to create songs that worked visually, even cinematically. Meanwhile, he met an artist friend of Dylan’s named Claudia Carr; they would soon fall in love and eventually marry.

“Jacques would tease him,” explains Claudia Levy today. “He appreciated Bob and loved his work, but didn’t venerate him. He’d say things to Bob like, ‘I hate that song of yours: “Lord, lord they shot George Jackson down”,’ and Bob would laugh.” When work was done, they’d head over to the Other End to drink and hang out.

Musician Steven Soles has been in the music racket since his teens and apprenticed with producer and songwriter Jeff Barry. Blessed with a set of mellifluous pipes, by June ’75 Soles was an up-and-coming solo artist. “I bumped into Bobby Neuwirth. He said, ‘Next week I’m playing the Other End,’ and he asked me if I’d play with him.”

Neuwirth also enlisted bassist/singer Rob Stoner and drummer/pianist Howie Wyeth. Then there were a string of guests who’d show up and play. “That was Neuwirth’s idea,” says Soles. “He’d have a band of people who could sing their own songs and people could come sit in. Dylan was there.”

After one show, Soles, Neuwirth, Stoner, Levy and Dylan went over to painter Larry Poons’ crib, joined by poet-turned-rocker Patti Smith and Texas musician T Bone Burnett. “We all played songs,” says Soles. “Dylan played us a number of songs that – as it turned out – would appear on Desire. The idea for The Rolling Thunder Revue was hatched by the two Bobs during Neuwirth’s little stint. This was spoken very clearly by Neuwirth to me.”

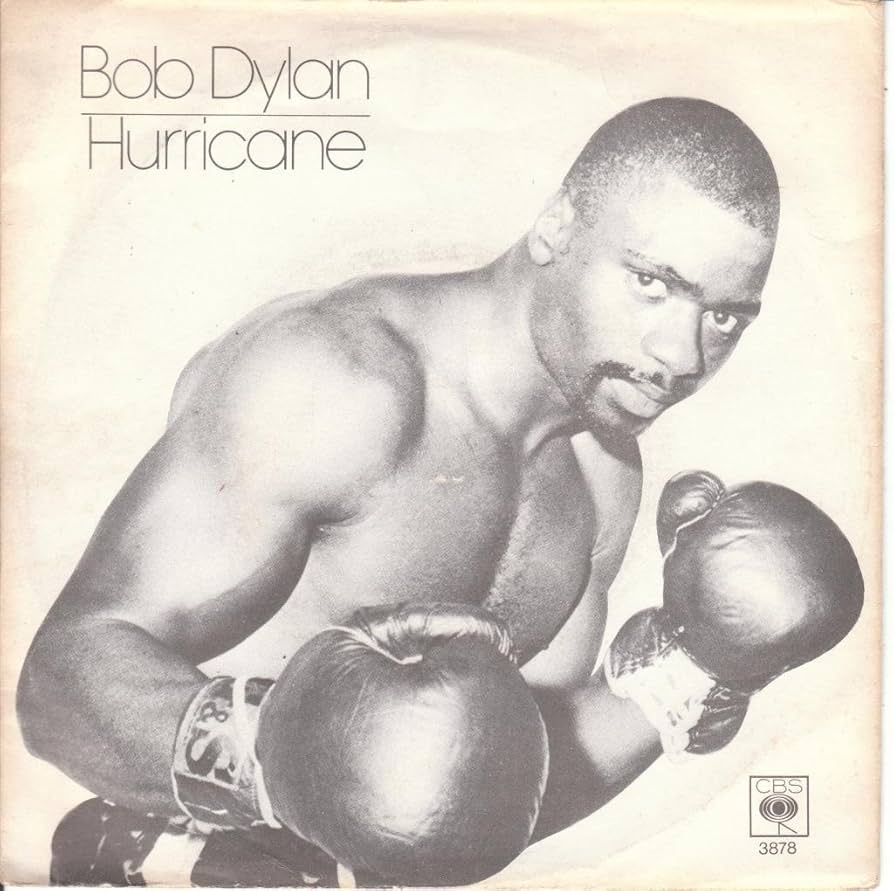

According to Soles, Dylan stayed up all night and the next morning went to visit boxer Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter in a New Jersey prison. Carter and another man named John Artis had been convicted of the 1966 murder of three patrons in a bar in Paterson, New Jersey. Carter wrote a memoir called The Sixteenth Round and had begun to amass supporters who believed he and Artis were innocent. One sent Dylan the book. He was moved by it and resolved to help Carter, declaring that “…the man’s philosophy and my philosophy were running down the same road.”

Muhammad Ali holds telephone during hookup with the State Prison at Clinton for a conversation with Rubin (Hurricane) Carter. Mrs. Carter (in white), daughter and others listened during benefit Rolling Thunder Revue Concert given by Bob Dylan at Madison Square Garden.

AT THE OTHER END IN EARLY JULY, Dylan joined old pal Ramblin’ Jack Elliott on-stage and jammed with Neuwirth and his growing guitar army, now expanded to include Bowie guitarist Mick Ronson and multi-instrumentalist David Mansfield. One night Patti Smith sat in and sang old folk songs.

On July 14, the first recording session for the new Dylan/Levy songs was held at Columbia Recording Studios, Studio E. Dylan wanted everything recorded live in the room – including the vocals. Don DeVito, a Columbia A&R man, by all accounts charming but inexperienced in production, was hired as producer. Engineer Don Meehan, who liked him nonetheless, maintains that DeVito was Columbia honcho Walter Yetnikoff’s “fair-haired boy”. Musicians included ex-Traffic man Dave Mason and his band, plus Rivera, harmonica player Sugar Blue, Vincent Bell on bellzouki, Dom Cortese on accordion and three background singers. The session yielded repeated takes and false starts of two songs, but nothing that ended up on Desire. Afterwards, Dylan and Levy headed out for Bob’s East Hampton, Long Island digs for more work. (The house was on Lily Pond Lane, which is name-checked on Desire’s Sara.) Things were not going as well as they’d hoped.

“It was a chaotic, crazy scene,” says Rob Stoner of the madhouse he entered on July 28, when called in by DeVito for the second session. “It was the most unconducive work conditions you can imagine.”

Stoner – a bassist’s bassist and a powerful singer and songwriter who had led legendary New York rockabilly band Rockin’ Rob And The Rebels – had already jammed with Dylan at the Other End, so he’d already had a taste. “The studio was full of well-known musicians and their hangers-on – everybody wants to hang out at a Dylan session,” he explains. “They had a caterer with food set up in another studio, everybody smokin’ and drinkin’ and eatin’. There was no way they were gonna get anything done and DeVito didn’t put his foot down. They’re goin’ through take after take, which is not the way Dylan likes to record. He likes to make the first complete take the one.”

While the cast had changed from the first session, now over 20 musicians were playing at once including Emmylou Harris on background vocals, Eric Clapton on guitar and the nine-piece UK soul outfit Kokomo. “Zimmy’s gone crazy,” Clapton is said to have muttered. “It sounded like everybody was on top of each other,” says engineer Meehan. “It was extremely hard to get any mix on it.”

But that wasn’t his only challenge – there was Zimmy himself. “Dylan didn’t want to overdub,” says Meehan. “I had to put up two mikes because his head would go side-to-side. I said, Bob, please – sing into the mike. Then I had to follow him around the studio, because he’d just start singing anywhere he felt like it. He’d stay in one place for a take, but then the next take he’d be somewhere else and Emmylou would have to follow him. I had to get as much isolation as I possibly could with the band playing live.”

Harris was acclimatising to Bob’s habits as well. “My energy was focused on singing on songs I’d never heard before. We had two microphones right together and the lyrics in front of us and I was waiting for direction. I had one eye on Dylan and one eye on the lyrics. He’d start the song and kind of poke me a little bit and I realised I was supposed to sing. (Laughs) Nothing was ever worked out.”

BY THE FOLLOWING NIGHT, July 29, Clapton was gone and the orchestra was pared down by half, but the sound remained overly busy and there were no usable takes. “At the end of the night, it was just me, DeVito, Meehan and Dylan,” says Stoner. “DeVito asked me flat out: ‘What should we do?’ I said the obvious: Let’s come back tomorrow night with the smallest possible group – the very opposite of this – and see if you get the opposite result – namely, success.”

Evidently Dylan appreciated Stoner’s blunt appraisal of the ongoing catastrophe. “Bob took me up on my offer: ‘OK, who should we get?’ I said, Let’s keep Scarlet, she’s got something unusual.”

Stoner also recommended drummer Howie Wyeth, who kept a crackling backbeat and was given to tasteful experimentation. Everyone loved Wyeth. “The personification of a laid-back, mellow musician,” describes Ratso Sloman. “He made you feel good; unlike some musicians, he had no ego.”

Stoner’s suggestion was the charm. By the fourth session, on July 30, the band was Dylan, Harris, Rivera, Stoner and Wyeth. This spare combo highlighted everyone’s strengths – Dylan’s percussive acoustic guitar, Harris’s angelic voice, Rivera’s soaring gypsy fiddle, Stoner’s agile, melodic bass, and Wyeth’s in-the-pocket drums. Then there are Dylan’s vocals, which may never have been better. He told Sloman that he’d been listening to Oum Kalthoum, the Egyptian songbird whose ornamental, melismatic style presages Dylan’s on Desire.

“I got into the flow of Dylan’s phrasing,” says Harris. “His singing, his phrasing, is extraordinary, not like anybody else’s. It’s so connected with the poetry of the lyrics.”

McGuinn concurs: “People criticise Dylan for not being a good singer, mostly because of ignorance – they don’t understand what he’s doing. If you listen to One More Cup Of Coffee or Sara, listen to those grace notes, he sounds like a violin. They’re in tune, they’re on time, they have meaning and emotion.”

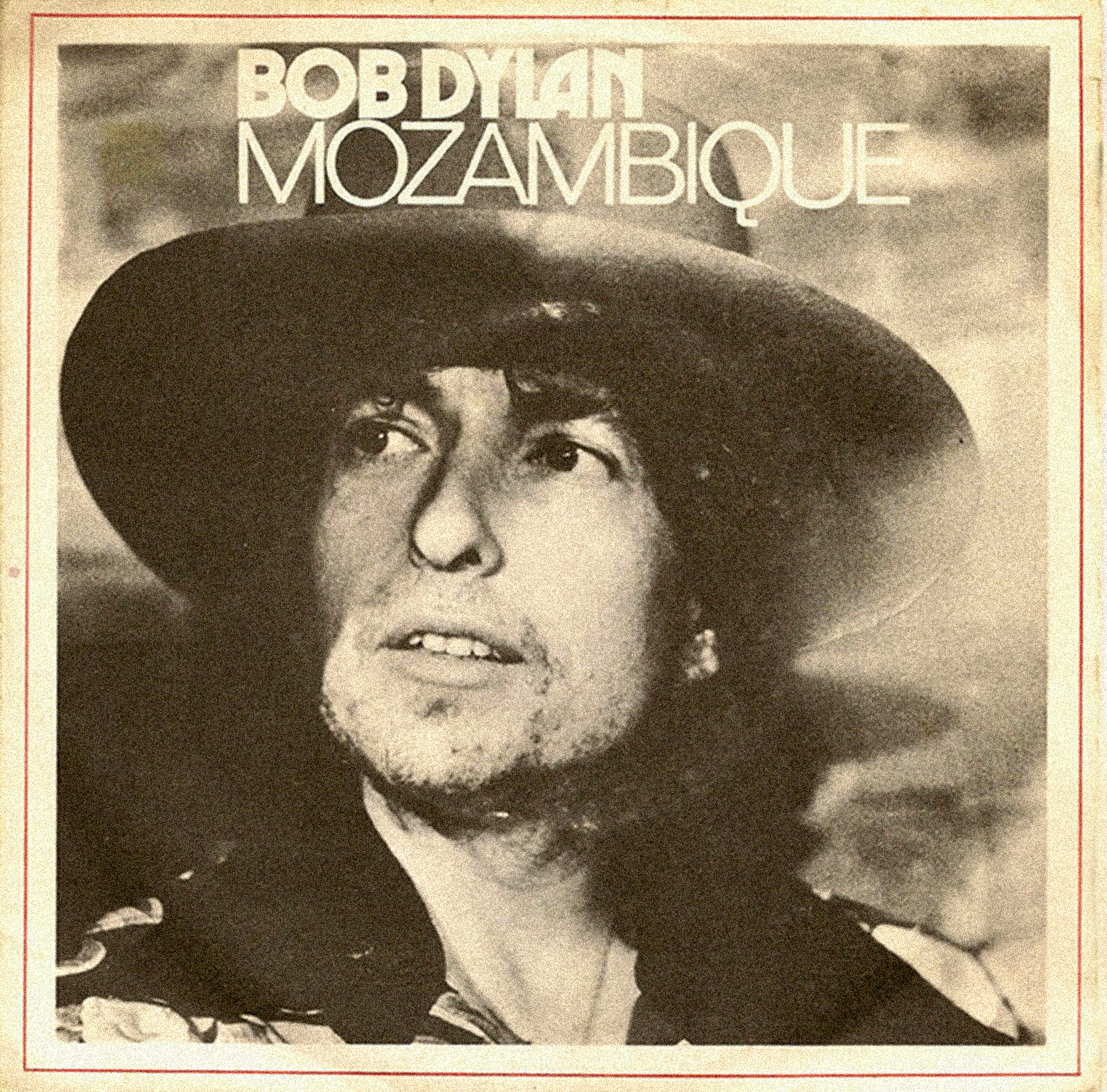

In that one night, they nailed four keepers of the nine that ended up on the album: Oh, Sister, One More Cup Of Coffee, Mozambique, and Joey – three more than in the previous three sessions. This quintet became the Desire template. Dylan’s eccentricities had the odd effect of increasing the musicians’ concentration and adding spontaneity.

“Bob does not count tunes off,” says Stoner. “He just starts playin’. There’s a couple tunes where the drums come in halfway through the first verse or are not in the first verse at all because Bob hadn’t counted the tunes in and he caught the drummer by surprise. The entire first verse of Mozambique, there’s no drums. Howie didn’t want to interrupt the take. He’d been asking technical questions like, ‘Is this gonna be a fade? Do I count this in?’ Bob gave him the look of death. I took Howie aside and said, Shut the fuck up. Don’t ask him anything. Just play, motherfucker.”

But if Stoner knew when it was best to keep quiet, he also knew when to leap uninvited into a void. “The beginning of One More Cup Of Coffee – that wasn’t arranged for me to do a bass solo. Scarlet wasn’t ready. Bob starts strummin’ his guitar – nothing’s happening. Somebody better play something, so I start playin’ a bass solo. Basically the run-throughs become the first takes.”

The fifth and final (or so they thought) session was on July 31. “First we listened to everything from the night before to make sure we weren’t being delusional,” Stoner continues. “Bob was pleased. Here we are, listening to what became Desire and realising that it was basically a jam by people who’d never played this stuff before.”

That night yielded Isis and the uncharacteristically revealing Sara (“Stayin’ up for days in the Chelsea Hotel/Writin’ Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands for you”). For the latter, Sara Dylan was invited to the session and Bob literally sang it to her, apparently for the first time. No one there can recall any palpable reaction on her part.

The team was excited and relieved – except for Harris, who asked to fix perceived flubs. “I got the chance to go back after hours and tried to improve some things and I realised it wasn’t possible. It was part of something that happened at the moment and you just couldn’t change it. It might have been more perfect, but it wasn’t as good. So I just said, That’s it. He knew what he was doing and this is how the baby came out. Honour the moment.”

Stoner got an inkling of what was in the works at that last session. “Bob comes over to me and says, ‘Hey man, you think you could do 30 minutes to open my show?’ He knew I was a front man. I said, Yeah, sure. What d’ya have in mind? He said, ‘I’m thinkin’ about doing some gigs and I need an opening act.’”

“I’m in the studio and I get a call from the producer saying, ‘Ya gotta erase the tapes!’”

Don Meehan

DYLAN WAS INVITED TO PERFORM on September 10 in Chicago at a public television tribute to his first producer, John Hammond, on a bill with The King Of Swing Benny Goodman and others. He assembled Rivera, Stoner and Wyeth. “There was no notice at all,” says the violinist. “I had no idea what a big deal it was gonna be. Once I did, it was terrifying. We rehearsed in the dressing room.” In addition to Simple Twist Of Fate, they debuted Oh,

Sister and Hurricane.

While everyone thought the next Bob Dylan album was in the can, someone realised that Dylan and Levy had made potentially libelous statements in Hurricane. Columbia’s legal department freaked. “One night I’m in the studio and I get a call from DeVito saying, ‘Ya gotta erase the tapes [of Hurricane]!’” recalls Don Meehan, who was stunned. “So I did. I had to erase, cut up everything.”

So on October 24, the core group of Dylan, Rivera, Stoner and Wyeth marched back into the studio to re-do Hurricane, this time with Steven Soles on second acoustic and Luther Rix on congas. Emmylou Harris wasn’t available, so Ronee Blakley, who’d received smash reviews as a Loretta Lynn-like country singer in Robert Altman’s Nashville, sang the harmony, joined by Soles and Stoner. It was a long session – 10 takes – that resulted in Dylan wearily stalking out before dawn. Two takes were spliced together to produce the master.

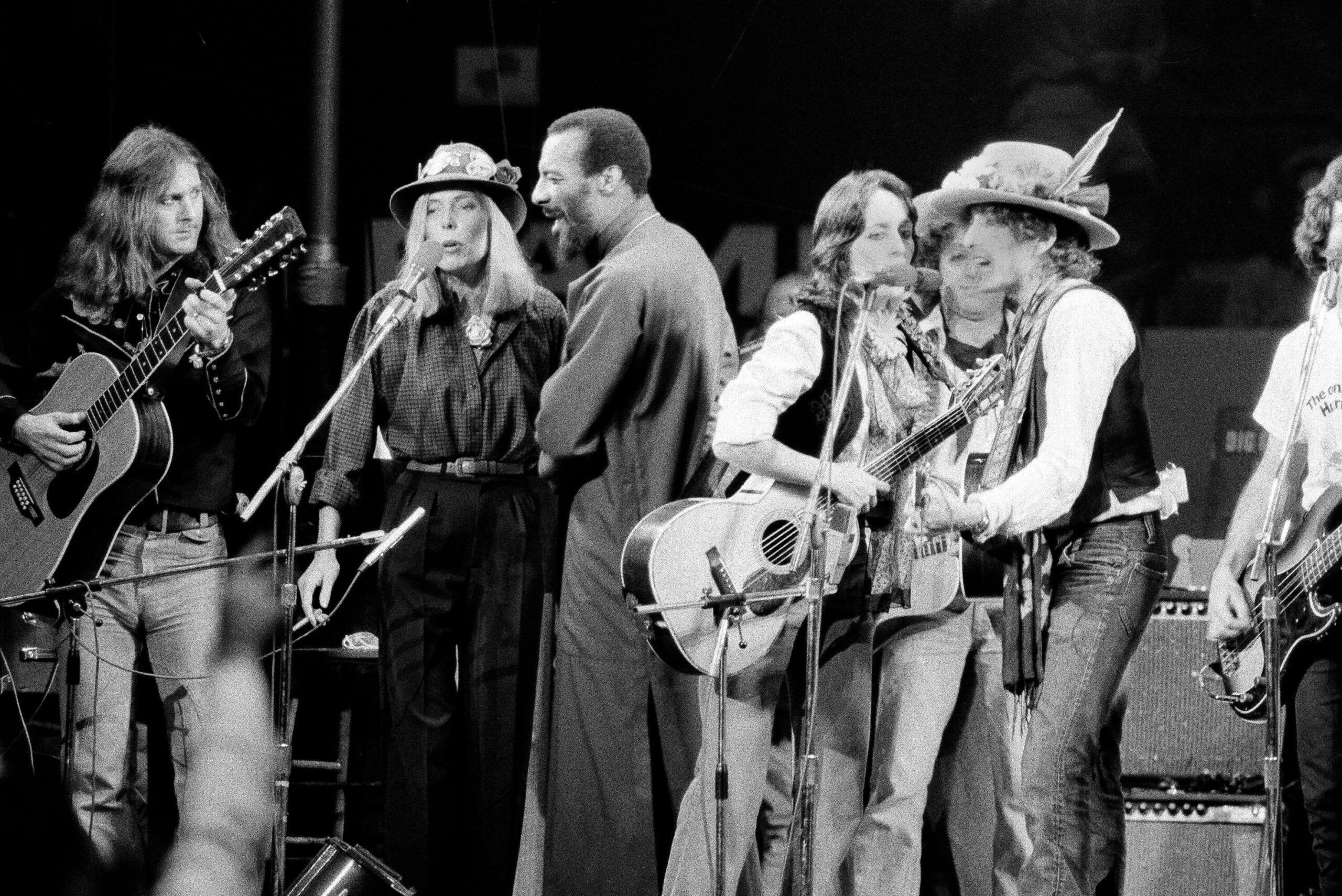

Within days, rehearsals for what became The Rolling Thunder Revue were scheduled at SIR studios on West 52nd Street in New York. Invited were a combination of the Desire band and Neuwirth’s Other Enders plus established stars: McGuinn, Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Neuwirth, Blakley, Stoner, Rivera, Wyeth, Soles, T Bone, Ronson, Mansfield, Rix, Allen Ginsberg.

A film crew would capture the proceedings, resulting in Dylan’s tour movie-cum-passion play Renaldo And Clara. Jacques Levy stage-directed the show and he and Stoner brought cohesion to the staging and music. But as Soles points out, “The thing itself was the boss – you give in to the process.”

For a month and a half, the first leg of The Rolling Thunder Revue toured the North-east and Canada, showing up in towns at short notice, selling out reasonably-sized halls – the

antithesis of arena rock. Roger McGuinn: “There’s always been a balance between art and commerce and the music business was getting commercial and not so artistic as it had been in the ’60s. This was a reaction, trying to balance the scale back on the side of art.”

The singers and band – dubbed Guam – were phenomenal, and Dylan – emerging from the creative crucible of Desire – was on fire. “He had such a big supporting cast, the pressure was off him having to be the star,” says Ratso Sloman. “On the other hand, having all those people there was a goad, so that he would blow everybody away every night. When he’s on, nobody’s as good as Bob.”

Dylan the ringmaster finally had his circus.

Roger McGuinn, Joni Mitchell, Richi Havens, Joan Baez and Bob Dylan perform the finale of the The Rolling Thunder Revue, a tour headed by Dylan, in Dec. 1975.

HURRICANE WAS RELEASED AS A SINGLE in November, did so-so on the US and UK charts and yet contributed to the public’s awareness of Rubin Carter’s case. Desire hit the shops the following January and reached Number 1 on the US charts and Number 3 in the UK. It’s an aptly-titled record that could easily have been called ‘Passion’. There are the odes to contemporary outlaws at war with society: Rubin Carter in Hurricane and Crazy Joe Gallo in Joey. Songs about obsessive love: Isis, Romance In Durango, One More Cup Of Coffee, Oh, Sister and Black Diamond Bay. And then there is Sara, the most blatantly autobiographical song in Dylan’s canon. Even Mozambique’s tourist brochure nostrums (“It’s very nice to stay a week or two”) add up to a terrific, hooky pop song.

Rob Stoner still praises the singularly strange sonic texture of the album: “It has none of the conventions of recordings of that day such as a lead guitar and standardised shit. Such is the method of Bob Dylan. That’s why he’s so unique – he changes the conventions. It’s got this mysterious, smoky feel – a lot of it is Scarlet.”

Despite misgivings at the time, Emmylou Harris has no regrets: “I wish there was more of that stuff in music because as grateful as we are for the technology to do things we couldn’t do early on, sometimes we get seduced trying to get things perfect when actually I don’t think there is such a thing. Desire just has a feel to it. It’s visual. Bob was like a painter who was throwing paint on a canvas, but he knew what he was doing.”

The Rolling Thunder Revue would roll on through May 1976. According to those who were there, Dylan seemed increasingly unhappy, despairing over the state of his marriage and wrapped up in the editing of Renaldo And Clara. But as the torrid, underrated live album Hard Rain from tour’s end shows, he never lost the edge that drove him to make music like no one else.

Ratso Sloman, who wrote the definitive Rolling Thunder account On The Road With Bob Dylan, remembers a conversation he had with him.

“When the tour was over we were at the Other End where the whole thing started and Like A Rolling Stone came on the jukebox. I said to him, Hey man, you didn’t even do your best song on this tour. “And Bob said, ‘Did I ever let you down on-stage?’ And he never did.”

This article originally appeared in MOJO 227

Images: Getty