Mojo

Presents

Damn The Torpedoes

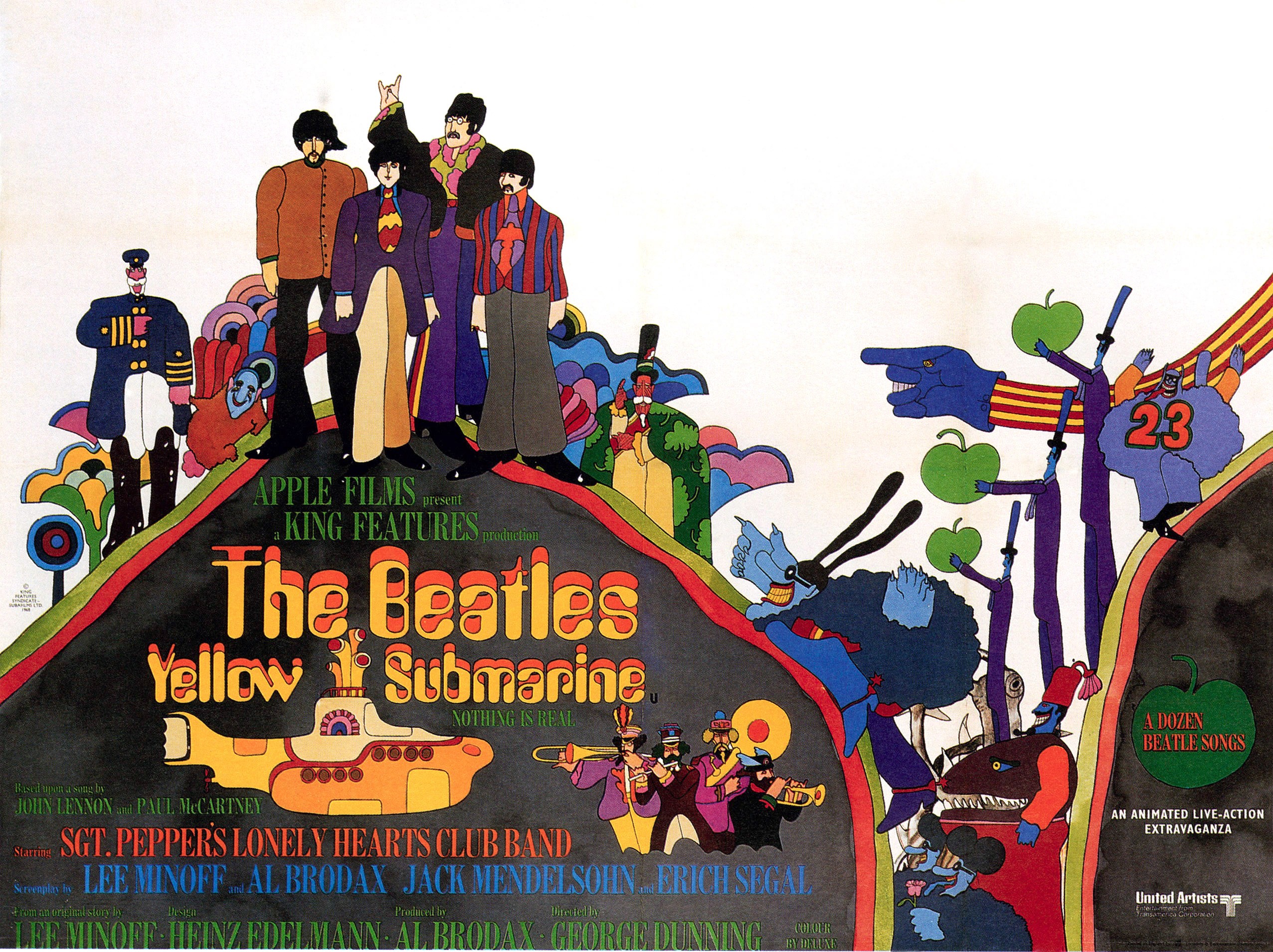

Full of holes but also hope; the target of hipster depth charges upon its release in 1968, but living on as a kind of psychedelic coelacanth: Yellow Submarine is still the most polarising Beatle product of all. In 2018, with the help of script scouse-ifier Roger McGough and famous fans, Mat Snow upped periscope.

The Beatles at TVC’s animation studios, participating in “Mod Odyssey,” a film about the creation of Yellow Submarine, November 6, 1967.

THE DOG & DUCK IN LONDON’S SOHO HAS seen some shenanigans. There was the time when Animal Farm was picked for the American Book Of The Month Club in 1946 and to celebrate George Orwell got stuck into the absinthe, a stash of which the pub had mysteriously acquired. Eight years later, Orwell’s fable about totalitarianism was adapted into a full-length animated feature film, the last made in the UK until, 14 years later, another fable about totalitarianism (and liberation therefrom) was brought to life by a team for whom a two-hour liquid lunch at the Dog & Duck plus gin and red wine refreshers back at the studio fuelled perhaps the greatest multisensory masterpiece of the psychedelic era – the Yellow Submarine movie. There was neither time nor inclination for those artists and animators toiling over every cel on the tightest of budgets, and an even tighter deadline, to drop acid; it was brown ale, Médoc and Gordon’s all the way.

“The production was so chaotic,” confirms Valentine Edelmann, daughter of the film’s late art director Heinz Edelmann. “To be in the middle of that was really tough for my father. It took him two years to recover and find himself again. For a long time afterwards he didn’t like us to speak about it at home.”

In truth, bad vibes had bedevilled the project from the start. In 1964, The Beatles had signed a three-picture deal with United Artists but, feeling they had better things to do than follow up 1965’s Help!, had yet to deliver the third. So when in 1966 Al Brodax, the producer of the US children’s TV cartoon series based on their zany capers, proposed a feature animation, UA would get their third picture and The Beatles need hardly get involved at all, not even voicing their characters.

Brodax contracted the production to the Soho animation house TVC, and here the conflict began. Thrilled by the creativity blossoming in both high and popular arts, fashion, design and more, TVC wanted to make something great, whereas Brodax wanted something quick. Not that the stogie-chomping Battle Of The Bulge veteran lacked artistic vision – he initially tried to hire Catch 22’s author Joseph Heller to write the script – but tensions rose as TVC developed an ever more elaborate feast for the eyes until, amid the threat of lawsuits and bankruptcy, the movie cut corners in a rush to make the July 1968 UK release.

“My dad was the kind of man always to see a work’s faults,” says Valentine Edelmann. “Like the final animated sequence at the end of the production has a stroboscopic effect but all the characters are standing still; it was the special effects man Charlie Jenkins who came up with the solution when there was no time or money left.”

For all the chaos, improvisation and tension of its production, Yellow Submarine does not fall short of TVC’s ambitions for it; inspired by not just The Beatles’ artistic adventurousness but the whole surrounding sociocultural ferment, the film captures the High ’60s in general and does full justice to the music in all its imagination, wit and colour. The Beatles themselves came to love it, even Paul McCartney, who had hoped for something very different.

“That’s what pissed me off at the end of it. Very little money and no credit.“

Roger McGough

OF ALL FABS SPIN-OFFS, THE YELLOW SUBMARINE film is surely the greatest. Now, 50 years after its original cinema release, it gets back to where it once belonged – on the big screen – where it blew its first generation of minds, including that of future XTC singer, guitarist and songwriter Andy Partridge: aged 14 when he went to the Swindon ABC when Yellow Submarine opened in 1968.

“Me and my mate Steve were so knocked out, we lay low after it was over and watched it three times,” he tells MOJO today. “We went again a couple of days later to watch it a few more times. It flipped my lid. I’d never seen anything like it. What was I looking at in that fantastic moving collage of images of Northern England in the Eleanor Rigby sequence? This was a different type of animation – it wasn’t Road Runner. Nor had I heard anything like it, especially It’s All Too Much and Only A Northern Song with that almost continuous jabber of different frequencies of psychedelicised sound smershed all over it.”

Competing over the school summer holidays with the Julie Andrews vehicle Star!, Yellow Submarine did respectable British box office. But released in America four months later it performed far better. Perhaps not because it tapped into the Zeitgeist but precisely because it didn’t – at least not any more. 1968 was America’s annus horribilis. The Tet Offensive; the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy; violence at the Democratic National Convention: on every TV screen in America the nation appeared to be tearing itself apart, culminating in the law and order backlash vote that propelled Richard Nixon to the White House in November. As Pauline Kael wrote that month in her New Yorker review of Yellow Submarine, “The movie is a nostalgic fantasy – already nostalgic for the happy anarchism of ‘love’. It finally goes a bit flat because love is no longer in bloom.” Yet less than six weeks later, Miller Francis of Atlanta’s underground paper The Great Speckled Bird asserted, “Yellow Submarine is rapidly on its way to canonisation.” Love may have wilted in Manhattan, but nationwide the hippy tribes coalescing into the Woodstock Nation were keeping the flower alive.

Then, of course, there were the kids. Kael again: The Beatles are “no longer the rebellious, anarchistic pop idols that parents were at first outraged by; they’re no longer threatening. They’re hippies as folk heroes… they have become quaint – such gentle, harmless Edwardian boys, with one foot in the nursery and the other in the boutique, nothing to frighten parents.”

Though the era of plastic mop-top wigs had passed and the time of discord and Yoko, Sgt. Pilcher and Chairman Mao already begun, The Beatles were more child-friendly than ever. And that was very much down to Paul McCartney. The pivotal Beatle year 1966 had marked the 10th anniversary of the death of his mother, and into his songwriting entered a new streak of melancholy, even morbidity (Eleanor Rigby), but also a more characteristically sunny nostalgia for a rosily recollected childhood (Penny Lane, When I’m Sixty-Four). McCartney was initially disappointed that the Yellow Submarine film was not in the classic Disney style; part of him wanted to regress to the time before the great loss of his life.

Nor was he alone in looking back. From the top down, urban planners, public bodies and private corporations were wedded to rebuilding the post-war world in rectilinear concrete, steel and plate glass, a white-heat-of-technology modernism reflected in the black polo neck sweater and polyester miniskirt. But from the bottom up, dedicated followers of fashion from 1965 onwards were increasingly tempted away from Mary Quant and Courrèges space age knock-offs by the offerings of Granny Takes A Trip, I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet, Hung On You and Biba. London happily swung between the seeming oppositions of the thrillingly if chillingly new and the half-nostalgically, half-mockingly old. It was the difference between The Beatles in their Sgt. Pepper satins and the sober, suited waxworks beside them on Peter Blake’s album sleeve.

ON THAT SLEEVE, SANDWICHED between Laurel and Hardy, lurks perhaps the Yellow Submarine movie’s most significant stylistic ancestor, the German-born US painter Richard Lindner, whose brightly coloured and clothed, half-comic, half-sinister characters blended the legacy of Otto Dix with poster-friendly pop art. In a similar vein but more Art Nouveau with a surrealistic twist, Heinz Edelmann’s illustrations in Germany’s Twen magazine commended him to take charge of Yellow Submarine’s visual style, most importantly its Beatle avatars with their outsize feet, legs and hands, grown-ups as seen from a child’s perspective. Not only did he give life to the scripted Blue Meanies but devised their army of snapping Turks, apple bonkers and the flying, crushing glove (surely the prototype of Terry Gilliam’s animated stomping foot in Monty Python, one of the TV classic’s several Beatle-isms). Alongside Robert Freeman, Klaus Voormann and Peter Blake, Edelmann completes the quartet of those who most inspirationally extended The Beatles’ brand into the visual medium.

“I was so obsessed with Yellow Submarine visually,” says Andy Partridge. “I started dreaming the Northern Song sequence where they psychedelicised and brought to life the solarised Richard Avedon posters, zapping an oscilloscope across the screen. I would draw the characters, then draw my own characters in that Heinz Edelmann style, making up stories parallel to Yellow Submarine.”

When Partridge unveiled his own psych-pop opus – XTC’s 1989 album Oranges & Lemons – he reached again for Yellow Submarine.

“I knew it had to have a bright pop art sleeve, with a dollop of Alan Aldridge – his sleeve to The Who’s A Quick One and cover of The Observer colour magazine of Paul McCartney in 1967 – a dollop of Milton Glaser, but mostly the style of Heinz Edelmann, whose books I had. That sleeve was our thank-you to our favourite pop artists.”

Partridge wasn’t the only future creator to fully submerge. Another was cartoonist and animator Matt Groening, creator of The Simpsons. His partner in Bongo Comics, MAD Magazine editor and fellow Sub nut Bill Morrison has now created a Yellow Submarine graphic novel, out this summer.

“I first saw Yellow Submarine on TV when I was around 13,” says Morrison. “I was blown away by the visuals and animation. It’s so bright and fresh and fun compared to today’s animation where super-real effects get to be boring after a while.”

A coincidence that TV’s first family are also yellow? “There is a lot of Yellow Submarine in The Simpsons,” Morrison says, “and the characters’ yellow is very close to the shade of the submarine. Matt Groening’s room at Bongo Comics is full of records; the Beatles section alone is massive, with bootlegs and interviews too. He can talk about them for hours.”

In an earlier Yellow Submarine tribute project, US comic artist Alex Ross reimagined a panorama of characters from the movie plus individual portraits of each Fab in a spectacularly three-dimensional style, as if Yellow Submarine were a Marvel superhero movie, a psychedelic Valhalla.

“The film was a surreal delight to me as a child; it had a hypnotic effect,” Ross tells MOJO. “In my teen years, it still seemed absolutely unlike anything else. It seemed wise – edgier, and more substantial than most ’80s entertainment. Today Yellow Submarine is magically exactly the same as it was to me as a child. It is charming, funny, engaging in all the ways that The Beatles seemed like the Marx Brothers in their other films, and it has the enormous advantage of the edge their music had by the psychedelic, colour-drenched late ’60s. I feel that it holds up against anything from the modern era.”

“I was totally obsessed with Yellow Submarine. At home I would draw my own characters in that Heinz Edelmann style.“

Andy Partridge

The Beatles posed with cardboard cutouts of their ‘Yellow Submarine’ characters at TVC animation Studios in London, 6th November 1967.

YET HOW BEATLEY, ULTIMATELY, IS YELLOW Submarine? They only appear in a brief live action coda, and where the group’s gravity had shaped the screenplays of A Hard Day’s Night and Help!, Yellow Submarine’s original script had passed through the hands of playwright Lee Minoff and then Erich Segal, the Yale professor of Greek and Latin literature who would later hit big with Love Story. It retained elements of both writers’ work – the know-all Nowhere Man Jeremy Boob was Minoff’s parody of British theatre director Jonathan Miller with whom he’d clashed on a Broadway production of Come Live With Me; the same character’s Latin gags were Segal’s.

What the dialogue needed was a higher than homeopathic dose of authentic Beatles flavour. Roger McGough was already famous in his own right as co-author with Brian Patten and Adrian Henri of 1967’s best-selling poetry collection, The Mersey Sound, and as a member of The Scaffold with John Gorman and Paul McCartney’s younger brother Mike McGear. At TVC’s insistence, he was the one Fab friend piped aboard.

“I knew The Beatles from the whole Liverpool cornucopia,” recalls McGough today. “And when I saw some of the early drafts by Erich Segal I realised why I was there. It was very American but also very metaphysical, with Greek references which sometimes work with the Blue Meanies but less with John or Ringo. So I came in and made The Beatles sound like The Beatles.”

Though initially brought in to doctor a few scenes, McGough became more involved and ended up writing the Sea of Monsters segment working alongside the animators (John: “There’s a cyclops.” Paul: “Can’t be. He’s got two eyes.” John: “Then it must be a bi-cyclops”).

“That’s what pissed me off at the end of it,” says McGough. “Very little money and no credit, even though [TVC’s] George Dunning wrote to Brodax saying I should get credit and more money for doing more work than I originally agreed. But no, credit would mean I would get subsidiaries. But it was a delightful thing to have done and I’m proud of it.”

Indubitably Beatley, of course, were Yellow Submarine’s four thus-far unheard songs. Three – McCartney’s All Together Now, a playtime sing-along boasting a cheeky depth charge in the couplet “Black white green red/Can I take my friend to bed”, plus Harrison’s Only A Northern Song and It’s All Too Much – were recorded in 1967 but deemed not good enough for Pepper, Magical Mystery Tour or even a B-side (“Apparently, they would say, ‘This is a lousy song, let’s give it to Brodax,’” the producer carped to MOJO in 1999). But time has been kinder, and It’s All Too Much, the most acid-drenched of all Yellow Submarine’s ‘originals’, has been elevated to the top table of the band’s psych output. Nearly as good, Lennon’s piano-pounding Hey Bulldog was the most recently recorded (February 1968), although the sequence it soundtracked was redacted from the film’s original US release. Both Edelmann and Brodax insisted that it didn’t fit.

Despite Lennon’s later characterisation of it as “all this terrible shit”, even George Martin’s orchestral interludes have aged well.

“A lot of people pass over side two of the soundtrack album,” says Andy Partridge. “But I think it’s perfection. So melodic, inventive and beautifully realised, from nabbing [Bach’s] Air On A G String for the character smoking the diversionary cigar, to Pepperland’s almost Ealing Comedy soundtrack.”

By the time the film hit the screens, The Beatles and rock were voyaging elsewhere, inspired by the autumnally ‘brown’ sound of The Band and dressed-down blues and folk. The intensity of Yellow Submarine’s sounds and images was already its own elegy.

“I was still wallowing in Magical Mystery Tour when The White Album hit, but The Beatles had moved on,” recalls Andy Partridge. “I must admit I wondered, Where has all the colour gone? Wind us down gently from Magical Mystery Tour, if you would! I went cold turkey. You couldn’t grasp how Pepper and Magical Mystery Tour and Yellow Submarine sounded so magical, couldn’t grasp how they did it. But you could grasp how they did The White Album – Oh, he’s turned his guitar up.”

This article originally appeared on Issue 297 of MOJO

Images: Getty