Mojo

Presents

Razor’s Edge

Imposing, outspoken messenger of black defiance, tragic Peter Tosh was reggae’s outlaw – no wonder he found an ally in Keith Richards. But his refusal to kowtow came with a cost – to his career, his health and his peace of mind. “Peter was just like any other human being,” friends and bandmates tell David Katz. “He had his good side, he had his bad side.”

Mystic Man: Peter Tosh performs live at The Oakland Coliseum in 1978 in Oakland, California.

June 17, 1978: 90,000 Rolling Stones fans packed Philadelphia’s JFK Stadium on a miserably damp Saturday afternoon. With Some Girls at the top of the album charts, many had camped through the sodden night to gain entry, and when Peter Tosh sauntered onto the stage with his Word Sound And Power band to open proceedings with the loping groove of 400 Years, many were already blotto on whisky, malt liquor and hash.

Tosh was promoting Bush Doctor, his forthcoming debut on Rolling Stones Records, which featured Keith Richards on a couple of tracks and a cover of The Temptations’ Don’t Look Back with Mick Jagger, but despite the blues-rock riffs of Tosh’s Indiana-born guitarist Donald Kinsey and Sly & Robbie’s indestructible rhythm section, these were unfamiliar sounds. Audience indifference was turning to hostility and missiles began to fly.

“With a Rolling Stones crowd, they’re so ready to see The Stones,” says Kinsey. “A lot of them had never even heard of reggae and they definitely hadn’t heard of Peter Tosh, so by the third song, people was getting impatient. I see an apple fly by my head and then a beer can and eventually a big sangria bottle.”

Tosh used karate moves to protect his head; grabbing the microphone, the normally unflappable singer cursed thousands of unheeding ears with a resounding *“Bumboclaat!” Through the barrage, Mick Jagger took the stage to intervene.

“Mick told the people Peter Tosh is his guest and that they need to respect this music,” continues Kinsey. “Then we went right into Don’t Look Back and the people really enjoyed the rest of the show.”

Later, Tosh would tell a reporter that the concert was “like Vietnam”. A Stones’ endorsement might open doors for an artist seemingly incapable of ingratiating himself, but Philadelphia was an unpleasant and unnecessary reminder that success and safety were not assured. Peter Tosh’s history had already taught as much. The lesson of his fate would be the same.

Don’t Look Back: Tosh performs live on stage with Mick Jagger in New York, 1978.

Born Winston Hubert McIntosh in 1944 in the remote district of Church Lincoln in northwest Jamaica, Peter never knew his philandering father. As his mother struggled to provide adequate care, the child spent weekdays with his Pentecostal aunt in Savanna La Mar. Running into a barbed-wire fence at the age of seven, he was nearly blinded – a foretaste of future entanglements with forces that would constrain him.

“I came from a poor family who wasn’t capable to give me a proper education at no level,” said Tosh, in a monologue that would feature in a 1992 biopic, *Stepping Razor: Red X. “But at the same time, my ambition and determination, my hopes and aspiration and my inner concept of creativity that was born in me showed me to help myself.”

Having learned some piano, then guitar, Tosh moved to Kingston during his teens, gaining a reputation as a street tough whose grabbing hands brought the nickname Peter Touch. He formed The Wailers with Bob Marley, Neville ‘Bunny’ Livingston and other more fleeting associates and although Marley became lead singer, Tosh provided the band’s harder edge. In 1966, he voiced Rasta Shook Them Up, the first Wailers song with a Rastafari focus. In the following year’s Treat Me Good, singing lyrics penned by Wailers mentor Joe Higgs, he proclaimed himself a “stepping razor” – the personification of a cutting blade, a dangerous man.

By then, Tosh had already fathered children with three different women (including Bunny’s sister Shirley) and clashed repeatedly with the authorities, arrested outside the British Embassy protesting Ian Smith’s declaration of Rhodesian independence and active in demonstrations supporting radical Guyanese academic Walter Rodney.

“Him just come on brave and say what him want to say and no care who vexed,” says Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, who produced the Wailers’ Tosh-led 400 Years and Downpressor. “Peter didn’t see himself as an artist to sing harmony; he have a star quality, but it did need somebody else to put out Peter’s message, because if I promote the two of them, Peter and Bob, it would be a big jealousy.”

Disgruntled with the increasing spotlight on Marley and fatigued by the band’s touring schedule, Tosh left the Wailers in 1973, shortly after Livingston. Seeking to extricate himself from the group’s Island Records contract, Tosh is said to have threatened label staffer Benjamin Foot (also the son of former governor, Sir Hugh) with a machete.

“I was a huge fan of Peter and respected him a lot, because he was truly brave — brave and crazy.” says Island boss Chris Blackwell. “But he never cared for me too much and called me Chris Whiteworst, and as soon as Don Taylor came in, he was managing Bob Marley and didn’t want Peter and Bunny around.”

“Jah sent me here to alleviate the Shitstem, the corruption that my people have been inoculated with.”

Peter Tosh

Freedom from Island did not bring Tosh the immediate breakthrough he craved. He played on sessions for Eric Clapton’s There’s One In Every Crowd in Kingston in late 1974, but his contributions were left off the final album and a proposed joint tour was abandoned. Still, crossover was clearly on Tosh’s mind when he flew to Oklahoma in May ’75 to record with Clapton’s band for RSO. But he was unhappy with the result and subsequently rebuilt the material with the Barrett brothers, Robbie Shakespeare, keyboardist Tyrone Downey and black American guitarist Al Anderson, lending the resultant Legalize It similarities to Marley’s Natty Dread. Atlantic, Bearsville, Buddha and EMI all expressed interest, but it took Blackwell’s intervention to broker a deal with Columbia, while Virgin licensed the album for Europe. Meanwhile, Tosh was grieving, and nursing a broken jaw, after his reckless driving had led to an automobile accident that left his 19-year-old girlfriend Yvonne Whittingham in a coma. She never recovered and died in February 1976.

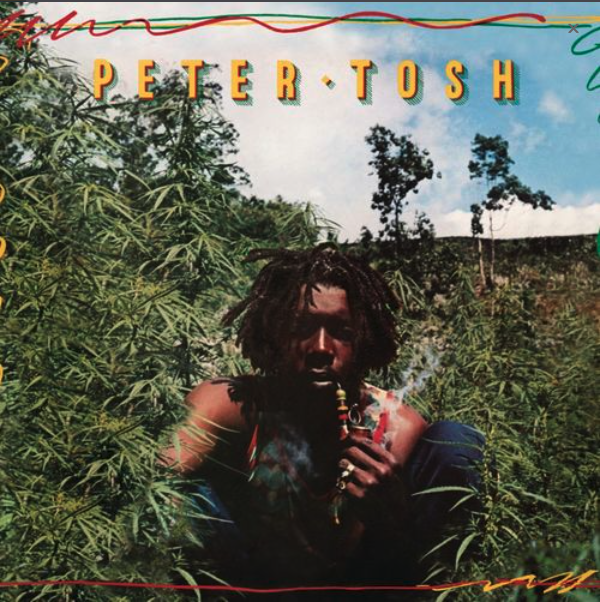

Tosh had already been beaten and jailed for marijuana possession. Uncowed, the cover of Legalize It showed him in a field of buds with lit pipe dangling. The anthemic title track was banned in Jamaica, but only emphasised that Tosh was forging his own path. “I happened to see Peter, Sly and Robbie at the studio one day,” says Anderson, who quit the Wailers to join Tosh’s touring band, “and I went, ‘Holy shit! This is completely different from Bob, a totally different momentum.’”

Inspired by Stevie Wonder and Earth, Wind and Fire, Dunbar and Shakespeare were trying to broaden Tosh’s appeal. “Our dream was to hear reggae being played on national radio,” says Dunbar. “We wanted to carry the music to that level.”

The recruitment of Donald Kinsey to augment Anderson would add a two-pronged rock edge: “Peter reminded me of Lightnin’ Hopkins,” says Kinsey. “He had a little mysterious way about him and when I went over to his apartment, he was like my brother from the past.”

Legalize It’s 1977 follow-up, Equal Rights, was even more combative than its predecessor. The title track proclaimed peace an impossibility until black and white shared a level playing field. Apartheid decried South Africa’s racist governance and African underlined the black diaspora’s shared heritage.

“Jah sent me here to help to alleviate the Shitstem, the dirty filth and corruption that my people have been inoculated with,” Tosh would claim. “It is only my duty to teach those who will learn.”

Concert audiences were growing, but Tosh was unceremoniously dropped by Columbia, sparking a bidding war. Which is when the world’s biggest rock’n’roll band – and their proprietary record label – intervened.

“Ronnie Wood was a really good friend of mine and I introduced Ronnie and Keith to Peter,” claims Al Anderson. “They fell in love with the guy and wanted to help.”

Jagger and Richards had been fans of Jamaican music since the early 1960s. More recently, The Stones had recorded Goat’s Head Soup in Jamaica in 1971 and Richards was spending more and more time there, having purchased a home in Ocho Rios. Signing Tosh made sense, but Ahmet Ertegun, head of Rolling Stones Records’ parent label, Atlantic, was hesitant; meanwhile, Virgin also had their eye on Tosh.

“I see a lot of misrepresentation on how we ended up with The Stones,” suggests longtime Tosh manager Herbie Miller. “Arma Andon was a Tosh fan at Columbia who hooked us up. We began negotiating with Earl McGrath [President of Rolling Stones Records], having sit-down conversations in New York, but Richard Branson wanted to sign Peter too. One day we drove over to Peter’s home on the outskirts of Spanish Town; Branson is barefoot with a leather bag, khaki shorts and a short-sleeved jacket like he was on safari. We sit on the ledge of Peter’s veranda and Branson said, ‘The only thing The Stones can offer you that I can’t is a tour with The Rolling Stones.’ And the rest is history: in April, Mick and Keith came to Jamaica on our invitation to see Peter perform, as they had not seen him previously: ‘Peter will be doing the Peace Concert, so why not come down?’”

1976’s Legalize It

The One Love Peace Concert took place at the National Stadium on April 22, 1978. During an era in which Kingston was riven by politically-motivated violence, rival gang leaders Claudie Massop and Bucky Marshall brokered a peace treaty, appealing to Bob Marley to end his exile by headlining the event. Tosh was not keen, doubting the treaty’s integrity, but eventually agreed. His performance before 30,000 people was an unprecedented tour-de-force with a lengthy diatribe, lambasting Prime Minister Michael Manley and opposition leader Edward Seaga for various shortcomings.

“None of us saw it coming and Peter was at his most brilliant oratorically,” says Herbie Miller. “He tied it to slavery, police brutality, education and the Americans killing out the ganja in Jamaica. He understood the neo-colonization process with more clarity than most, which is why he was able to speak about it as a part of a reggae concert.”

The performance sealed the deal with The Stones, but the uncompromising militancy would cost Tosh dearly. After the Some Girls tour, on September 11, he was beaten, this time within an inch of his life, at Half Way Tree police station after being apprehended with the tail-end of a joint. With his skull burst open and a broken arm, Tosh survived by pretending to be dead.

Once his wounds healed, Tosh performed at the São Paulo Jazz Festival and embarked on a postponed European tour. Meanwhile his appearance with Jagger on Saturday Night Live helped (You Gotta Walk) Don’t Look Back reach the UK Top 50 and Billboard’s Hot 100 and add momentum to the *Bush Doctor album. Yet, although Tosh and Robbie Shakespeare enjoyed close friendships with Keith Richards, there was tension beneath the surface; you can hear it in the title track of 1979’s Mystic Man, which flung a barb at The Stones’ druggy lifestyle. Mainly recorded at Dynamics with Geoffrey Chung, whose brother Mikey now handled lead guitar duties, the album’s roots reggae core was obscured by overloaded horn parts from Saturday Night Live band members, Ed Walsh’s synth lines and choral backing vocals from Gwen Guthrie, Brenda White and Yvonne Lewis. Naturally, the disco excess of Buck-In-Hamm Palace made the biggest splash, despite Tosh’s antipathy to the form. “Peter used to call it devil music,” laughs Miller. “But when Sly dropped that on him, he made a great song.”

After the commercial excesses of Mystic Man, 1981’s Wanted Dread And Alive was far more roots. Following a theme, the expletive-laden Oh Bumbo Klaat was also banned in Jamaica; Tosh said he experienced temporary paralysis caused by an evil spirit, which he dispelled by uttering the title. Guide Me From My Friends had a similarly paranoid feel, indicative of Tosh’s troubled state of mind.

“In the middle of the night, I was attacked by evil forces, spiritual evil forces that cause my mouth to cease from function, cause my hands and legs to cease from moving,” Tosh told reggae writer Roger Steffens. “Is only my mind that was in function and my two eyes… I could not tell a man nothing or ask a man to do anything to help me; I was on the brink of what you call death.”

“On our way to master Mama Africa we actually got kidnapped; there were people with M-16s.”

Chris Kimsey

Tosh was beginning to drive away his allies. After making disparaging comments about the Stones in the press, his friendship with his label patrons would rupture when his extended occupation of Keith Richards’ Jamaican home ended in eviction, Tosh threatening violence before beating a retreat. Afterwards, Tosh pruned his inner circle, replacing Herbie Miller with Marley’s former manager, Danny Sims, and recruiting a new band for Mama Africa, released by EMI in 1983. There was a new producer, too: former Stones engineer Chris Kimsey.

“I was a huge ska fan when I was a kid,” says Kimsey, “and Keith used to play reggae all the time when I was working with The Stones, so the whole musical element really intrigued me. I had never been to Jamaica before and when Danny Sims met me at the airport, we went straight to Channel One studio and I just sat in the control room for three or four days and grooved on the music until I was invited to sit at the console.”

The album’s breakout track was a restructured Johnny B Goode, which reached the UK Top 50 and MTV’s Top 100. Initially, Donald Kinsey had struggled to add anything sufficiently original to Chuck Berry’s rock’n’roll classic, then “about 3 o’clock in the morning, it hit me: the bassline, the vocal melody, the Almighty gave it to me. I was so excited, I woke everybody up. The next day I told Peter, ‘We need a hit record. Let me get the band and lay the track, brother. And if you don’t like it, burn it up.’”

Tosh toured *Mama Africa for a full nine months, largely to rave reviews. Yet Kimsey says the album was nearly scuppered by disgruntled Tosh associates. “We were driving to [the airport to] go back to New York to master it and we actually got kidnapped; there were people with M-16s that accused Danny [Sims] of trying to steal the music. I said, ‘I’m just a record producer and I’ve come down here to capture this wonderful music; if you don’t let me go and master it, it will never come out.’ So they let me go, but they kept Danny! It was probably some Rastafari friends of Peter who were concerned that the New York mafia had come down to screw him. But, Peter, as we all know, was into some funky things as well.”

Tosh had a new love interest – Marlene Brown, 17 years his junior – but his health was poor, beset by chronic migraines and a stomach ulcer. After the Reggae Super Jam, held at the National Arena in December 1983, he essentially stopped performing live. Gripped by internal demons, he physically attacked those closest to him, including two of his sons and managerial assistant, Copeland Forbes.

“It was so depressing to come off of such a high and to see what happened to him after that,” laments Donald Kinsey. “Peter reached one of the highest heights of his career and then his involvement with certain people, that just turned all of his friends away from him. He called me and wanted me to work on the *No Nuclear War album, but it wasn’t the Peter that I know.”

“There was only one Peter Tosh and he was a very creative person but if you didn’t hang out with him, you couldn’t judge him,” says drummer Santa Davis, who joined Tosh’s band after *Wanted Dread And Alive. “Peter was just like any other human being: he had his good side, he had his bad side.”

Sessions for No Nuclear War were disrupted by a protracted lawsuit with EMI over unauthorized releases in South Africa. Finally completed in July 1985, Tosh’s only studio album with 100 per cent Jamaican musicianship mixed the defiant Nah Goa Jail and Fight Apartheid with the wary Lessons In My Life and although Vampire was aimed at politicians, it also spoke to Tosh’s frame of mind.

EMI would eventually be forced to pay $250,000 compensation, but the album’s release was seriously delayed; together with radio announcer Jeff ‘Free-I’ Dixon, Tosh was also trying to purchase national radio station JBC, intending to relaunch it with a Rastafari perspective. Meanwhile, crossing paths with Dennis ‘Leppo’ Lobban was the worst thing that ever happened to the singer. Trench Town-born Lobban had spent several years in prison for aggravated burglary and other serious charges and upon his release became a regular visitor to the singer’s household. Then, in the summer of 1987, Tosh’s participation in a JBC radio broadcast brought dramatic repercussions.

“Peter was getting close to making a settlement with EMI,” says Santa Davis. “One day he was in New York and he called Barry G on the radio and said, ‘Me want to make some millions off of this,’ and all of Jamaica was hearing it.”

“Peter was dealing with issues that were serious and I still love my brethren,”

Santa Davis

On the night of September 11, Lobban and two associates crept into the house where Santa Davis, Wilton Brown and Michael Robinson were visiting Tosh and Marlene. “Peter heard a sound by the gate, then me just see Leppo say, ‘Nobody move, this is a stick up,’ and tell everybody to lay down on the ground,” says Davis. “I get the sensation of blood, like me smell death, then Leppo put a .357 Magnum ‘pon my head and said, ‘No partiality, Dread,’ and take $350 out of my pocket and take off a watch.”

In the middle of the robbery, Free-I and his wife Joy walked in; after bullets were fired and the gunmen fled, Tosh, Free-I and Brown were dead and the others nursing serious gunshot wounds.

Lobban remains in prison today and although his accomplices were never officially identified, they were allegedly killed after being linked to Tosh’s murder. It was a tragic and ignoble end for the revolutionary singer, whose work inspired a younger generation of artists including Luciano, Bushman and South Africa’s Lucky Dube, and empowered his contemporaries.

“Peter Tosh was the launching pad for Sly and Robbie,” emphasizes Sly Dunbar. “I really thank him for bringing us to the frontline as a rhythm section, for introducing us to America and Europe and for giving us the freedom to play.”

The perpetual outsider who refused to conform to Jamaica’s societal norms, Tosh rejected the easy categorisation of standardized reggae, rendering him an unsung early World Music pioneer. And if his inner torments caused the abrasiveness that alienated the international music press and ultimately, many of his closest associates, the uniqueness of the man is surely reflected in his uniquely inspiring and enduring repertoire.

“Peter was dealing with issues that were serious and I still love my brethren,” Santa Davis concludes. “Even though he’s not here today, spiritually, I feel connected the same way.”

Images: Getty